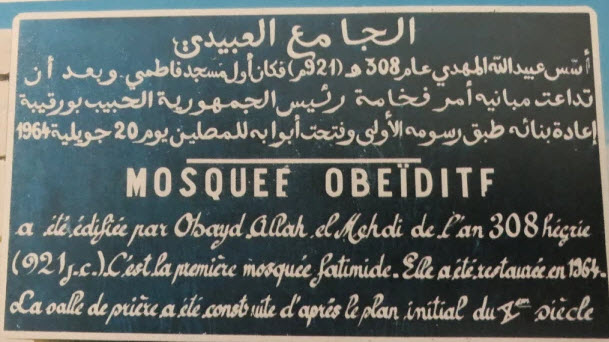

Named after the Prophet’s daughter, the Fatimids, Mawlana Hazar Imam’s ancestors, established their empire in 909 in Qayrawan, North Africa, when Imam al-Mahdi was proclaimed Caliph. The Fatimid Caliphate remained in North Africa during the reign of Imams al-Mahdi (r. 909-934), al-Qa‘im (r. 934-946), and al-Mansur (r. 946-953). Imam al-Mu’izz (r. 953-975) founded the city of Cairo which subsequently became the capital of the empire.

Qayrawan, the metropolis of North Africa and the capital of Ifriqiya (modern day Tunisia and eastern Algeria), had long been a major centre of Sunni scholars belonging to the Maliki and Hanafi schools of law. There was also a small community of Shia to which Ibn al-Haytham (not to be confused with the scientist who came to be known as Alhazen) belonged. Shortly after 909, Ibn al-Haytham gave the oath of allegiance to enter the Ismaili da’wa, and thereafter, “set out on the path to a long distinguished career as a scholar and writer in the service of the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs” (Jiwa, The Fatimids p 18-19).

After the establishment of Fatimid rule in Qayrawan, “public debates were held between the leading Ismaili da’is and the foremost scholars of the city’s Maliki Sunni community. Among the themes that Ibn al-Haytham notes as subjects of debate were the principles of imamate, the nature and scope of guidance in the Muslim community, the stature and virtues of Ali b. Abi Talib and questions related to the interpretation of the Qur’an as well as some issues of Greek philosophy. He also observes the etiquette with which the debates were held, with the da’is promising security to their opponents despite the opposition of their claims” (Jiwa, The Fatimids p 19).

Nasir Khusraw notes in his Safarnama, that the Fatimid court at Cairo “engendered some of the liveliest theological and intellectual debates in the Muslim world. Astronomers, poets, grammarians, physicians, legal experts, theologians, and other members of the intelligentsia were brought to the capital and given generous stipends and materials for their creative work” (Hunsberger, The Ruby of Badakhshan p 156).

“Knowledge (‘ilm) and wisdom (hikma) are, according to Ismaili belief, gifts from God, revealed to humanity through His prophets” (Halm, The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning and p 17). “It was the practice of Ismaili missionaries from the very beginning of the da’wa to pass on the ‘wisdom’ to their pupils in teaching sessions known as ‘sessions of wisdom’ (majalis al-hikma)” (Ibid. p 24). These were private sessions for Ismaili converts, teaching the esoteric Ismaili doctrines.

From the earliest days of the Ismaili da’wa in North Africa, participation in the majalis al-hikma was a regular occurrence in the lives of the followers. “During the reign of Imam al-Mahdi bi’llah, responsibility for the delivery of the majalis was delegated to Aflah b. Harun al-Malusi, a native Berber and a notably distinguished and gifted da’i. Imam al-Mahdi appointed him, first, as the chief judge of Tripoli, and thereafter he was promoted to the position of chief justice. In a custom that would continue for decades, the chief justice was also appointed … chief da’i” (Jiwa, The Fatimids p 94-95). Aflah presented the majalis al-hikma in the Fatimid capital of Mahdiyya on a weekly basis.

“The office of the chief da’i became one of the most eminent positions in the Fatimid lands, the gateway through which the knowledge and guidance of the Imam was conveyed to the Ismaili faithful. The chief da’i was also responsible for the administration of the da’wa both within the Fatimid realms and for the communities of Ismailis across the Muslim world. All local and regional da’is, who would hold majalis of their own for the benefit of their communities, were directed by the chief da’i.

Ibn al-Haytham’s first-hand account notes that the presence of women in the majalis was commonplace, as was the participation of people from different walks of life including shepherds, labourers, and carpenters. He also notes that Aflah would tailor his lessons to make them relevant to his audience” (Jiwa, The Fatimids p 94-95).

“Aflah al-Malusi died sometime before 923 during the reign of al-Mahdi. Decades later, another chief da’i, the esteemed Qadi al-Nu’man, began a career whose legacy is still felt today.

Al-Nu’man was born around 903 into a learned family in Qayrawan. He entered the service of Imam al-Mahdi in 925, serving the first four Fatimid Caliph-Imams in various capacities. In 948, Imam al-Mansur appointed al-Nu’man to the position of chief judge of the Fatimid state.

Imam al-Mu’izz, who succeeded his father in 953, “met the leading chiefs of the Kutama [tribe] to encourage the pursuit of knowledge. When he was told that the Kutama were diligent in gathering together after every Friday prayer to listen to lectures and participate in discussions and debates, he replied:

“This is what we wish from them and others, for it is their fortune, the amelioration of their situation, and the completion of God’s favours upon them… We wish to make them all luminaries by whom people are guided, beacons who illumine their path with their light, and the learned ones from whom they acquire knowledge” (Ibid. p 92-93).

Qadi al-Nu’man states:

When the Commander of the Faithful al-Mu’izz li-Din Allah opened the gate of mercy for the believers and turned his attention to his followers by his benefaction and grace, he gave me books on esoteric knowledge [ilm al-batin] and instructed me to read out from them in a session every Friday at the palace…

According to al-Nu’man’s eyewitness accounts, the yearning for knowledge that the Imam sought to instill in his followers was something that he himself seems to have felt deeply. The qadi writes how al-Mu’izz would regularly engage in a variety of conversations and debates, and that he would often request books and manuscripts to read…”(Ibid. p 92-94).

The majalis at Imam al-Mu’izz’s palace became increasingly popular and believers gathered there every Friday after the communal prayers.

More on the Ismaili da’wa and da’is at Ismaili Gnosis.

Sources:

Shainool Jiwa, The Fatimids, The Rise of a Muslim Empire, I. B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2018

Heinz Halm, The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning, I. B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 1997

Alice Hunsberger, Nasir Khusraw, The Ruby of Badakhshan: A Portrait of the Persian Poet, Traveller and Philosopher, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2000