Nasir Khusraw (1004- ca.1077) was born in Qobadiyan in the district of Marv in the eastern Iranian province of Khurasan. He did well at school, learning Persian and Arabic as well as sciences, literature, mathematics, philosophy, religious sciences, and history. Following his family’s tradition, Nasir joined the government bureaucracy in a financial capacity, perhaps as tax collector. He enjoyed to travel and “relished the opportunity to see new places and admire the accomplishments of the human hand and mind. In his travels, he turned his keen eye towards both the physical and administrative structures put in place by each society, such as city walls, irrigation canals and road surfaces in one, and taxation conditions, employment practices and shop rental policies in another” (Hunsberger, The Ruby of Badakhshan p 5).

“But, for Nasir Khusraw a more urgent current ran under such delights of the world, namely his aching desire to have some purpose, some answer to the question of why all this exists” (Ibid). At the age of about forty, Nasir experienced a restlessness, a spiritual upheaval, that he describes in his Safarnama (‘Travelogue’) as “a powerful dream that shocked him out of his ‘forty years’ sleep’. This restless searching and inner discontent lasted until it all came together in the conviction that the answers to these ultimate questions could be found in the doctrines of the Ismaili Shi’i faith” (Ibid).

“The poet reports that he began his consciously organised search for wisdom … a search which involved reading books and listening to those who were learned in an array of fields, including both physics and metaphysics…. His spiritual quest is to find the most perfect human being in the entire world. Since every genus and species in the created world – from the starry heavens down to minerals deep within the earth – has its own exemplar, among humans there must also be someone ‘most noble.’ But all his questioning of the learned men in the major schools of Islamic thought proves fruitless” (Ibid. p 56).

“Particularly troubling for Nasir Khusraw is the ‘verse of oath’ in the Qur’an (48:10), because it seems to give special status to those who lived at the time of Prophet Muhammad, those who were able to personally give their allegiance to God and His Prophet. This refers to a specific historical event in the early years of the Prophet’s ministry. Six years after the migration from Mecca to Medina (the hijra), the Prophet and a number of his followers gathered under a tree in a place called Hudaybiyya. When the Prophet asked for the allegiance of his followers, they all placed their hands on the Prophet’s hand … thus demonstrating their fealty. That God accepted their oath is evident in the words, ‘God’s hand is over their hands.’

‘Once I happened to read in the Qur’an the ‘verse of oath,’

The verse in which God said that His hand was stretched above,

Those people who swore allegiance ‘under the tree’

Were the people like Ja’far, Miqdad, Salman and Abu Dharr. I asked a question from myself, what happened to that tree, that hand;

Where can I now find that hand, that oath, that place? …

Whose hand should we touch when swearing allegiance to God?

Or should not (divine) justice treat equally those who came first and those who came later?

Was it our fault that we were not born at that time?

Why should we be deprived of personal contact with the Prophet,

thus being (unjustly) punished?

(Ibid p 56-58)

“According to Nasir, there must always be someone at whose hand the covenant of God could be pledged. This, he decided, was the Imam descended from the Prophet’s family, al-Mustansir of Cairo, the sovereign of a mighty empire” (Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages p 135).

He resigned from his job and went on a journey in search of knowledge and the essence of life, setting off on March 5, 1046,1 keeping a detailed record of his travels in his Safarnama.

Beginning his seven-year journey westward through northern Iran, across Armenia and Azerbaijan, down through Syria to Jerusalem, and other cities of the region, Nasir Khusraw arrived in Cairo in August 1047.2 He spent three years in Cairo, the capital of the Fatimids and the heart of Ismaili power and intellectual life, where he studied Ismaili doctrines with leading scholars, including al-Mu’ayyad a-Shirazi (d. 1078), whom he credits for his conversion to Ismailism. Hunsberger states “Al-Mu’ayyad is the person who helps this seeker of wisdom find the knowledge he has been searching for.

He [Al-Mu’ayyad] said:

Cease worrying, the jewel has been found in thy mine.

Beneath the ideas of this world there lies an ocean of Truth,

In which are found precious pearls, as well as Pure Water.

This is the highest Heaven of the exalted stars.

Nay, it is Paradise itself, full of the most captivating beauties.”

(The Ruby of Badakhshan, p 62-63).

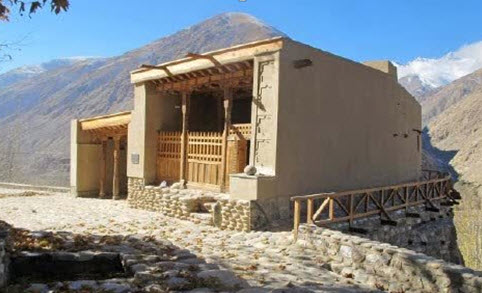

Nasir returned home as head of the Ismaili administration of his province. However, his successes put his life in danger causing him to flee from his native land to Yumgan in the mountainous region of Badakshan, to the court of an Ismaili prince, where he stayed for the remainder of his life, composing his numerous works.

The Ismailis of Badakshan (now divided between Tajikistan and Afghanistan) along with communities in Hunza and other northern areas of Pakistan, as well as in the Sinkiang (Xinjiang) region of China, regard Nasir Khusraw as the founder of their communities. A literary tradition based on his writings sustained the Ismaili community of Central Asia in their faith in the areas under the Soviet system, when they were not permitted to practise their faith, and did not have direct contact with the Imam of the time or with other Ismaili communities.

As head of the Ismaili da’wa, Nasir produced a number of works on Ismaili doctrines including Wajh-i din (The Face of Religion), which is considered “the most explicit in terms of religious instruction, offering a full explanation of Islamic commandments and duties and their esoteric meaning or ta’wīl.” (Hunzai, Pearls of Persia p12).

The main corpus of his poetry is collected in the Diwan, comprising poetry in the qasida form relating to a wide range of ethical, theological, and philosophical themes. Hunsberger notes that the main purpose of Nasir Khusraw’s poetry is “to open the reader or listener’s inner eye to universal truths and thereby save their souls from the Hell of ignorance” (The Ruby of Badakshan, p xvii). Forty poems were translated by P. L. Wilson and G. R. Aavani in 1977 and in 1993, Annemarie Schimmel translated and discussed key themes in selected verses.

A rare copy of the Diwan was gifted to Mawlana Hazar Imam during his Diamond Jubilee visit to western Canada in May 2018.

God calls you to the heavens;

Why have you thrown yourself into the pit?

To ascend to the highest heavens, craft for yourself

Feet out of knowledge and wings out of devotion.

Divan, 22:39-49

published in Ruby of Badakshan p 90

Further reading: The Concept of Knowledge in Nasir-i Khusraw’s Philosophy at Ismaili Gnosis

Sources:

1Alice C. Hunsberger, Nasir Khusraw, The Ruby of Badakhshan, I.B. Tauris, London, 2000 p 92

2The Institute of Ismaili Studies Secondary Curriculum Muslim Societies and Civilisations Volume 2 p 245

Faquir Muhammad Hunzai, “The Position of ‘Aql in the Prose and Poetry of Nasir-i Khusraw,” Pearls of Persia, Edited by Alice C. Hunsberger I.B. Tauris, London, 2012

Shafique N. Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages, Oxford University Press, 2007