The term ‘Islamic art’ refers to visual arts produced in Islamic regions by a variety of artists and for diverse consumers, not necessarily by and for Muslims. Sheila Blair explains that “while some types of Islamic art, such as Qur’an manuscripts, mosque lamps or carved wooden minbars (pulpits), are directly concerned with the faith and practice of Islam, the majority of objects considered to be “Islamic art” are called so simply because they were made in societies where Islam was the dominant religion.”

The term does not refer to a particular style or period, but covers a broad scope, encompassing the arts produced from Spain to India for fourteen-hundred years, in diverse regions using a variety of materials and patterns.

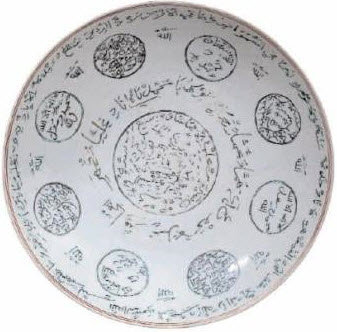

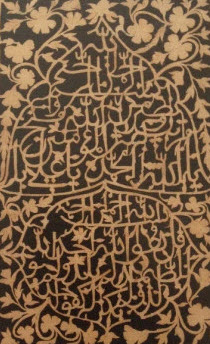

Titus Burckhardt (d. 1984), member of the Master Jury of the first awards of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, stated that “the art of Islam is essentially a contemplative art, which aims to express above all, an encounter with the Divine Presence.” Islamic art then, is the external expression of inner spirituality. Verses of the Qur’an are engraved or embossed on buildings such as the masjid, madrasa, and shrines of Sufi saints as well as on everyday objects such as household utensils, cloth, wood, inspiring the remembrance and contemplation of God.

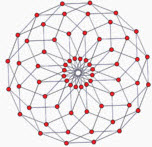

Islamic art first and foremost reflects the concept of tawhid, Divine Unity through a variety of forms such as the circle, the basis of complex geometrical patterns. The circle – which has no beginning and no end and thus symbolises infinity – was considered to be the perfect geometric form, from which complex patterns were developed.

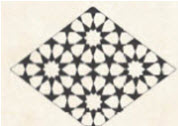

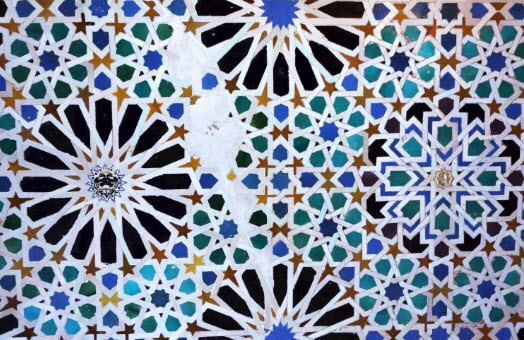

Geometric patterns were combined, interlaced, and arranged in intricate combinations, thus becoming one of the most distinguishing features of Islamic art. In places of worship, where a wealth of these geometric patterns can be found, one could contemplate the infinite nature of God simply by looking at the walls or the ceilings. The un-ending repetitions also add to the concept of God’s infinity while demonstrating that “in the small, you can find the infinite” (Burckhardt).

The orderliness of the geometric patterns conveys an aura of spirituality and a sense of transcendent beauty. The centric arrangements were used in order to avoid focal points, resonating with the view that the “Absolute is not centred in a divine manifestation but whose presence is an even and persuasive force throughout Creation” (Burckhardt).

With its geographic spread and long history, Islamic art was subject to a wide range of regional and even national styles within the various periods of its development. One of the distinctive styles that developed is the arabesque – employing abstract intertwining vine, leaf, and plant motifs, often implying an infinite design with no beginning or end.

Arabesque is often combined with interlacing geometric and other decorative patterns; perhaps the vegetation evoked themes of paradise, described in the Qur’an as a garden.

Developed in the Eastern Mediterranean regions once controlled by the Romans, the arabesque acquired its own distinctive forms in Islamic lands and became a hallmark of Islamic art produced between the tenth and the fifteenth centuries. In order to describe it, Europeans coined the word “arabesque,” literally meaning “in the Arab style,” in the fifteenth or sixteenth century when Renaissance artists began to incorporate Islamic designs in book ornament and decorative bookbindings. Over the centuries the word has been applied to a wide variety of winding, twining, meandering vegetal decoration in art. This art style became popular due to its adaptability to virtually all media, from paper to woodwork and ivory.

Light is the most common symbol across all religious traditions signifying the Divine. There are numerous verses in the Qur’an that use the metaphor of light (nur), which in the Shia interpretation are linked to the principle of Imamat.

Photo: Archnet/Gary Otte

Seyyed Hossein Nasr states that “to grasp fully the significance of Islamic art is to become aware that it is an aspect of the Islamic revelation, a casting of the Divine Realities (haqa’iq) upon the plane of material manifestation in order to carry man upon the wings of its liberating beauty to his original abode of Divine Proximity.”

“…in Islamic thought, … beauty and mystery are not separated from intellect – in fact, the reverse is true. As we use our intellect to gain new knowledge about Creation, we come to see even more profoundly the depth and breadth of its mysteries.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam

Ottawa, Canada, December 6, 2008

Speech

Sources:

Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Religious Art, Traditional Art, Sacred Art (PDF)

Sheila Blair, “Islamic Art,” Islamic Art and Architecture ,Yale University Press, 1996

Titus Burchhardt, Art of Islam: Language and Meaning, World Wisdom, 2009