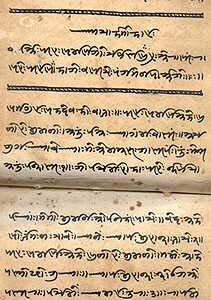

From the Sanskrit jnana meaning ‘contemplative knowledge,’ Ginans are a vast corpus of poetic compositions whose authorship was attributed to preachers, Pirs, sent by Imams residing in Iran to the Indian subcontinent around the eleventh century to teach the Ismaili interpretation of Islam to non-Arabic speaking people.

At the time, the field of devotional poetry was flourishing in the subcontinent, with figures such as Narasimha Maeta (15th century), Mirabai (1498-1557), and Narhari (17th century), Kabir (1440-1518), and Guru Nanak (1469-1539). Additionally, a tradition of mystical poetry was developing among the Sufis in the subcontinent. Hence the traditions of the bhaktas, sants, Sufis, and Ismailis of the Indian subcontinent were all interconnected.

The Ginan literature “came to be perceived within the community as a kind of commentary on the Qur’an” (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 30). Several Ginans are stories or parables that are meant to be interpreted mystically such as Kesri sinh swarup bhulayo (The Lion Forgot his Lion-form), which describes a lion who has forgotten its true identity on account of its upbringing among a flock of sheep. Listen

Many Ginans are supplications (venti) for spiritual enlightenment and vision (darshan, didar) such as Hun re piasi tere darshan ki (I Thirst for a Vision of You), which draws on the symbol of a fish writhing in agony outside its home in water. Listen

Unch thi ayo (Coming From an Exalted Place) is a lament of the soul’s fate in the material world and a plea for the intercession of Prophet Muhammad. Listen

Several Ginans portray the ego as “the greatest deterrent to the soul’s submitting to the Guidance of God’s appointees and achieving gnosis” (Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages p 173). In his composition Satgur padhariya tame jaagjo, Pir Satgur Nur, the earliest Pir to work in the Indian Subcontinent, remarks: “Awake! For the True Guide has arrived.” In verse 4 of this Ginan, Pir states:

“The Guide says: Slay the self (man ne maaro). I shall hold you close, for indeed, a precious diamond has come into your grasp. Behold it, O chivalrous one, contemplate in these words” (Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages p 173).

In the composition titled Vaek Moto, Pir Shams “extols the virtues of knowledge, ‘ilm, and urges the faithful to plumb the depths of esoteric wisdom conveyed by the Imams” (IIS)

Pir Shams states:

“What can the guide do if, despite holding the lamp of gnosis in hand, the intrigues of the capricious self cause the believer to tumble into a dark well?” (Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages p 173).

In verse 7 of the Ginan Sami tamari vaadi maahe, Pir Shams explains

“Only when the obstinate self’s inane excuses are cast off can the guide exercise his transforming effect and the could acquire divine recognition (Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages p 260 n 30).

“This effect is picturesquely compared to that of a fragrant sandalwood tree in a forest filled with margosa trees. Just as the presence of the sandalwood tree makes the surrounding margosas redolent, so does the perfume of the guide’s knowledge transform the disciples” (Satgur bhetea kem janie). However, simple contact with the Guide, the Imam, does not guarantee the transfer of knowledge. Unless the self has first submitted to the Guide, the believer is no better than the bamboo trees that neighbour the sandalwood trees, but are not affected in the least by its scent (Aj te amar avea v.2, Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages p 174).

Sayyid Imamshah states: “Slay the self and make it your prayer rug. Brother, remain steadfast in contemplation” (Pir vina par na pamie, verse 2, Virani, Ismailis in the Middle Ages p 260 n 28).

Sources:

Ali S. Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment, The Ismaili Devotional Literature of South Asia, I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., London, 2002

Azim Nanji, The Nizari Isma’ili Tradition in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, Caravan Books, New York, 1978

Shafique N. Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages, Oxford University Press, 2010

Vaek Moto, The Institute of Ismaili Studies