International Day of Light commemorates the anniversary of the first successful operation of the LASER (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) on May 16, 1960 by Theodore Maiman, a physicist at Hughes Research Laboratories in Malibu, California.

“The study of light and its properties has revolutionised every field of science and has involved all the major figures of science from Ibn Al Haytham to Einstein” (UNESCO). Among al-Haytham’s monumental contributions was his understanding of the crucial role of visual proportions, which influenced Renaissance Europe’s science and art.

Abu Ali al-Hassan ibn al-Haytham (965-1039), a distinguished philosopher, physicist, and mathematician was born in Basra, Iraq, where he earned a reputation for his knowledge of applied mathematics. Claiming to be able to regulate the flow of the Nile, he was invited by the Fatimid Caliph-Imam al-Hakim (r.996-1021) to assist with a hydraulic project at the current location of the Aswan Dam. However, al-Haytham was forced to concede the impracticability of the project. He spent the remainder of his years in Fatimid Cairo, residing close to the Al-Azhar mosque and centre of learning, founded by the Fatimid Caliph-Imam al-Mu’izz (r.953-975), working on theories of vision and light.

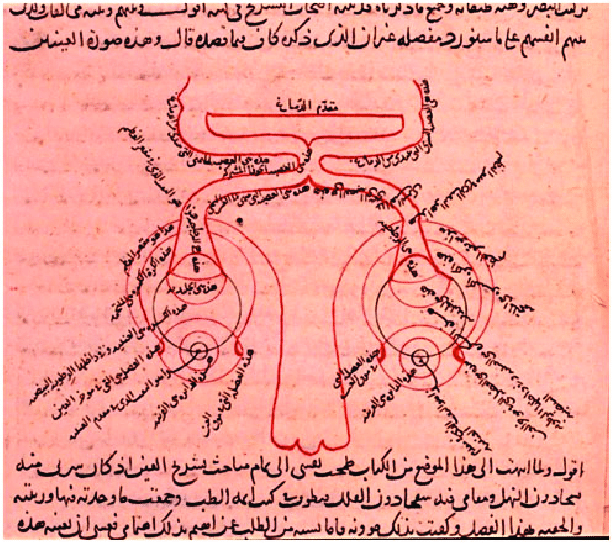

Early theories of vision claimed that in order to see an object, light emanated from the object into the eye. Although many challenged this theory, it remained until the year 1000 when Ibn al-Haytham developed a scientific theory of vision that proved earlier theories of light travelling in straight lines, but from the eye to the object and not vice-versa. He also developed mathematical models of reflection and refraction to prove his theories, urging others to repeat his experiments to verify his results and conclusions.

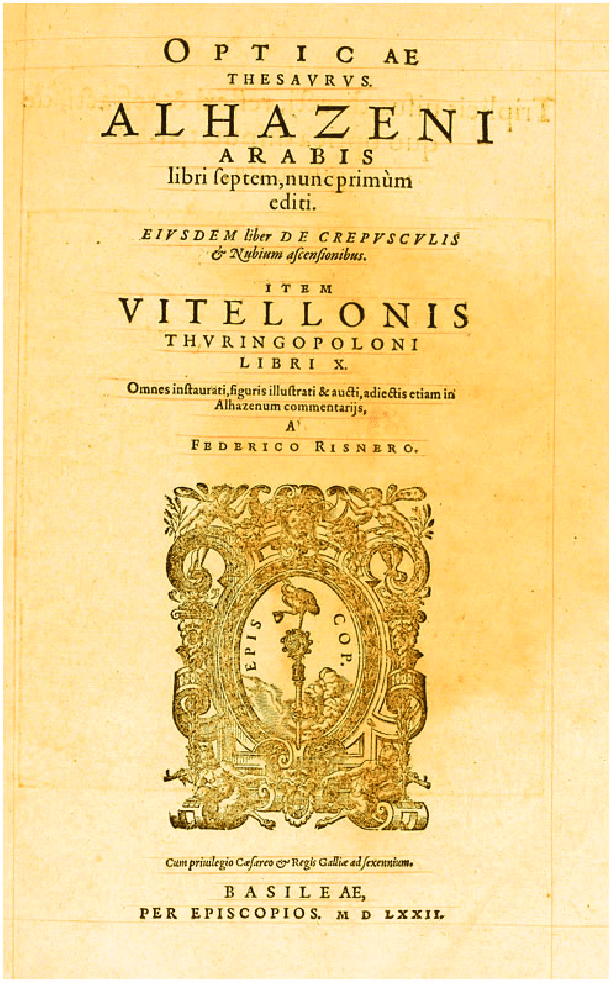

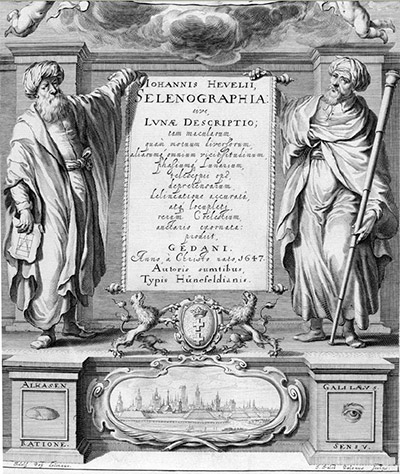

Ibn al-Haytham is considered the earliest proponent of the modern scientific method earning him the title of “the first scientist.” He wrote several works including his influential seven-volume text Kitab al-Manazir (‘Book of Optics’), which was translated into Latin as De Aspectibus (‘Visible Aspects’) and became popular in Europe where he was known by his Latinised name Alhazen or Alhacen.

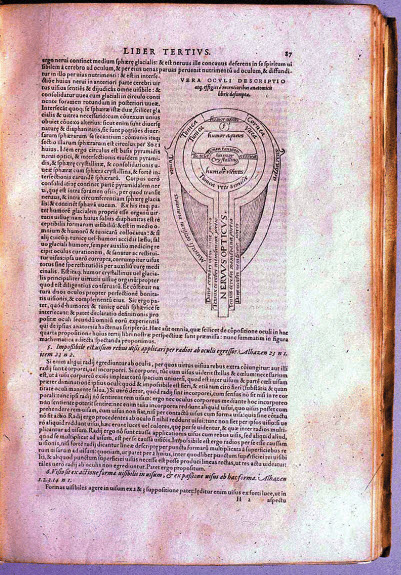

The De Aspectibus was printed by Friedrich Risner (d. ca. 1580) in 1572, as part of his collection Opticae thesaurus. The English philosopher Roger Bacon (d. 1292) wrote a summary of De Aspectibus into a form that became historically important and remained the standard theory of vision until the work of Kepler (d. 1630).

Marshal notes: “Unlike many of his time or predecessors, Alhazen was a diligent experimenter, verifying unproved theories first by experiment. He observed the magnifying power of spheres and lenses, and experimented with cylindrical, concave, and parabolic metal mirrors… His geometrical or optical theories were demonstrated by diagrams which aided lens- and spectacle-makers to produce reasonably accurate results…Kepler conceived the optical construction which gives an inverted image, and Scheiner made the first telescope which incorporated this inverted-image principle suggested by Kepler. This is probably the earliest intellectual contact between Alhazen and modern scientists. Kepler was a contemporary and friend of Galileo” (Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets, February 1950).

“Few mathematical and scientific writings in the Middle Ages have been as influential as those of Ibn al-Haytham, whose works were translated into Latin, Italian, and Hebrew…. His mathematical works influenced Roger Bacon, Frederick of Fribourg, Kepler, Snell, Descartes, and Huygens and many others” (Rashed).

Among al-Haytham’s monumental contributions was his understanding of the crucial role of visual contrasts (for example, the contrast of the brightness levels explain why we cannot see the stars during the daytime) and proportions, which impacted aesthetics:

“For sight perceives beauty only from the forms of visible objects which are perceptible to it; and these forms are composed of the particular properties that have been shown in detail; and sight perceives the forms from its perception of these properties; and therefore, it perceives beauty from its perception of these properties.”

Ibn al-Haytham, Kitab al-Manazir, vol. 2, cited in Beauty and Islam, p. 22

Gonzales states that with this new conception of vision and perception “appeared a new aesthetics, the aesthetics of light that was notably developed through the great programme of cathedral-building and the decisive problem of perspective in paintings” (Ibid p. 23).

The Latin texts of the Book of Optics were translated into Italian in the 14th century, titled Prospettiva (‘Perspective’), which was studied in the school of Padua in Italy. Biagio Pelacani da Parma (d. 1416), a renowned Italian philosopher, mathematician, and astrologer, assimilated al-Haytham’s work, and in turn influenced pictorial representation in Renaissance art and spatial design in architecture.

Ibn al-Haytham’s works influenced art theorist and architect Leon Battista Alberti (d. 1472), author of the treatise On Painting (Della Pittura); the sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti (d. 1455); and the artist Piero della Francesca (d. 1492). Al-Khalili notes that “they harnessed Ibn al-Haytham’s discussion on perspective to help create the illusion of three-dimensional depth on canvas and in friezes.”

Al-Haytham wrote over 200 treatises and books but only about 50 have survived although most of them have not been translated from Arabic. His numerous notable works include Risala fi al-dawʾ (‘Treatise of Light’), al-Hāla wa-qaws quzaḥ (‘On the Halo and the Rainbow’), Ṣurat al-kusuf (‘On the Shape of the Eclipse’), and al-Ḍawʾ (‘A Discourse on Light’). In mathematics, he wrote about the area of crescent-shaped figures and on the volume of a parabolic revolution (formed by rotating a parabola about its axis). He also wrote on astronomy, music, ethics, politics, and poetry, and “defended astrology as a science based on mathematical proof…”(Sabra). Certain ophthalmology terms originated from the Latin translation of Alhazen’s Arabic text, such as retina and cornea.

In 2014, the Hiding in the Light episode of Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, presented by astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, focused on the accomplishments of Ibn al-Haytham, who came to be known as “father of optics.”

In 2015, on the one-thousandth-year anniversary of Ibn al-Haytham’s Book of Optics, UNESCO declared it the International Year of Light in his honour.

A lunar crater is named after Ibn al-Haytham as is the asteroid 59239 Alhazen, in recognition of his enormous contribution to science.

“Today, as we use laser beams to manipulate atoms, stimulate neurons with light or convey information in entangled photons, it is worth recalling that the foundations of this field were laid down around 1,000 years ago by Ibn al-Haytham” (Al-Khalili).

~*~

“Extract from Islamic history, from Islamic philosophy, the great names, the great thinkers, the great astronomers, great scientists, great medical figures who have influenced global knowledge.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam Aga Khan IV in conversation with Adrienne Clarkson at the Prize for Global Citizenship, Toronto, Canada, September 21, 2016

Video of the conversation

Sources:

Abdelhamid I. Sabra, Ibn al-Haytham, Harvard Magazine

Anthony Carpi, Annee Egger, Alhazen: Early experiments on light, Visionlearning

Jim Al-Khalili, In retrospect: Book of Optics, Nature, International Journal of Science

O.S. Marshall, Alhazen and the Telescope, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets, Vol. 6, No. 251, p.4, The SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System

Roshdi Rashed, A Polymath in the 10th Century, Science Magazine

Valerie Gonzalez, Beauty and Islam, Aesthetics in Islamic Art and Architecture, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2001