“The fundamental reason for the pre-eminence of Islamic civilizations lay neither in accidents of history nor in acts of war, but rather in their ability to discover new knowledge, to make it their own, and to build constructively upon it. They became the Knowledge Societies of their time…The spirit of the Knowledge Society is the spirit of Pluralism—a readiness to accept the other, indeed to learn from him, to see difference as an opportunity rather than a threat.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam

Speech

In pre-Islamic times, the recitation of poetry was the mark of artistic achievement. The prevalent form was the qasida – a long monorhyme (aa, ba, ca) that was used in praise of someone or basic rhetoric. Subsequently, it was used to teach morals as well as praise God and the Prophet.

An important aspect was the growing awareness of the potential expressiveness of the human voice, considered a reflection of the soul’s mysteries and feelings. As Islam spread, the music of the various communities became entwined with the traditions of the conquered lands.

The elite, who were enriched by the influx of wealth, sought amusement that was best expressed in song and music. New artistic forms emerged elevating the status of musicians and singers including women, who were known as qayna, who received their musical training from the most famous musicians of the day. Hence the accomplished qayna could “conduct gracious conversations with guests and gladden their hearts with songs and instrumental music” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 30). Some of the accomplished artists include Khawla bint al-Azwar (7th century), Azza al-Maila (d. ca. 707), Atika bint Shuhda ( 8th century), among others.

For the first three centuries after the emergence of Islam, Medina became a musical centre in the Arabian peninsula attracting talented artists noted in some of the earliest surviving works on music including the Book of Melodies by the esteemed poet Yunus al-Katib (d. 765), Book of Diversion and Musical Instruments by Abu’l Qasim Ubayd Allah (d. 911), and Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems by al-Mas’udi (d. 956). In his Book of Songs, one of the most celebrated works in Arabic literature, the poet and historian Abu’l-Faradj al-Isfahani (d. 967) compiled a collection of poems from the pre-Islamic period to the ninth century, all set to music along with biographical details about the authors, composers, and singers. He noted that “in a society avid for knowledge the study of music became obligatory for every learned person; music was one of the topics frequently discussed by people in all walks of life ” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 26).

The prose writer al-Djahiz (d. ca. 868-9), in his masterpiece the Book of Animals, discusses the “characteristics of sounds and the effect of music on the souls of men and animals (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 25).

Ya’qub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (d. ca. 870), a philosopher, mathematician, physician, and musician, included music in the mathematical sciences that “prepare the student for higher studies of philosophy and for knowledge of the wonders of creation…The science of harmony in its broadest sense is central for understanding the complex network linking music to all attributes of the universe” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 49). Al-Kindi, in his work Book of Sounds Made by Instruments Having One to Ten Strings, explains that instruments help create harmony between the soul and the universe.

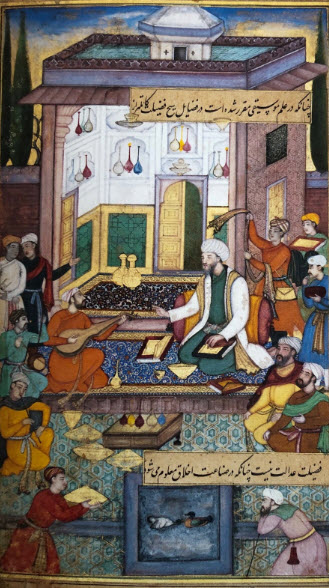

Al-Kindi’s theory was further developed by the Ikhwan al-Safa (Brethren of Purity), an anonymous tenth-century group of authors based in Basra and Baghdad, Iraq, who compiled an encyclopedic work – Rasa’il Ikhwan al-Safa’ (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity). Seeking to show compatibility of Islam with other religions and intellectual traditions, the Ikhwan drew on diverse schools of wisdom including Babylonian, Greek, Persian, and Indian traditions.

The Ikhwan occupied a prominent position in the history of scientific and philosophical ideas in Islam owing to the wide intellectual reception and dissemination of diverse manuscripts of their Rasa’il.

Although the exact date of the Rasa’il and the identities of its authors remain a mystery, some historians situate this brotherhood to the eighth century, attributing the compiling of the Rasa’il to the early Ismaili Imams Jafar al-Sadiq, Abd Allah (Wafi Ahmed), or his son Ahmad b. Abd Allal (al-Taqi); others situate the Ikhwan to just before the founding of the Fatimid dynasty in North Africa in 909. Daftary notes that the Ismaili origin of the Rasa’il was recognised by Paul Casanova in 1898, “long before the modern recovery of Isma’ili literature” (Daftary, The Ismai’ilis their History and Doctrines p 246).

In the section on music, the Ikhwan discuss that “musical tones [naghamat] have a spiritual effect on souls” (Epistles, “On Music,” p 84). Music, notes the Ikhwan, “reflects the harmonious beauty of the universe… Musical harmony conceived according to the laws of the well-ordered universe helps man in his attempt to achieve spiritual and philosophical equilibrium…the proper use of music at the right time has a healing influence on the body” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam, p 50). The Ikhwan devote special section to the making and tuning of instruments.

In his work The Ethics of Nasir, a philosophical treatise on ethics, social justice, and politics, the Persian philosopher Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (d. 1274) proclaims that after the nearness to God, ‘no relationship is nobler than that of equivalence as has been established in the science of music’ (Spirit & Life Catalogue p 167).

Sources:

Music in Islam

Epistles of the Brethren of Purity, “On Music,” Edited and Translated by Owen Wright, Oxford University Press in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2010

Amnon Shiloah. Music in the World of Islam. Wayne State University Press. Detroit.1995

Farhad Daftary, The Isma’ilis: Their History and Doctrines, Cambridge University Press, 1990

From the Manuscript Tradition to the Printed Text: The Transmission of the Rasa’il of the Ikhwan al-Safa’ in the East and West, The Institute of Ismaili Studies